Interview with M. Giesser, Director and Communications Designer

Shillington plays host to incredible industry lectures every semester, offering our students the opportunity to learn from and meet experienced professionals across the multitude of practices within the field of design. Mike Giesser, Director of Melbourne’s M.Giesser studio, recently presented a lecture to the Shillington Australia campuses offered an in-depth insight into how a professional designer runs their own studio and he’s not stingy on the details.

True leaders possess a capacity to share and nourish their community, free of the desire to harbour trade secrets or keep their practice shrouded in mystery. The desire not only to inform but to enhance community comes across in the way Mike talks about his work as a designer.

In his recent lecture and in this interview, he generously talks at length about his practice in a frank and honest way. In this interview, he discusses why mornings are his most productive times, how he manages client relationships and the process of producing incredible work which really focuses in on the needs of the client, without getting caught up in anxieties about originality. Take a minute to kick back and put your feet up as we dive deep into the brilliant mind of M. Giesser.

What does a typical day at M. Giesser look like for you?

Get up at 5am, make coffee, slide upstairs to the studio, read emails, decide whether I can safely choose to ignore them or whether I need to reply right away.

I tend to ignore them if I can as the best “creative” time for me is this period between 5 and 10am. But since I’ve been doing more work with overseas clients, it just means they’re often waiting for me to get back to them by the time I get up. Most of my local clients don’t start calling/ emailing until after 10am, so that allows me to get fresh tracks on the creative slopes before the snow (my mind) turns slushy.

The rest of the day is always a bit different and is determined by what I’ve got on. Some days, I’m juggling a number of different projects and other days I’m stuck into the concept development of one project, which means I shut off everything so I can focus. When I’m at the concept development stage, I try and plan my time around that and block out 2 – 3 full days in a row where that’s all that I’m doing. I’ll put that project down for a few days to catch up on other things and then pick it back up with fresh eyes and go at it again for another 2 days.

It’s taken me years to figure out how I work best, which sounds odd but when you’ve been in other studios for 15 years, it’s not really up to you and it takes a while to find your own groove.

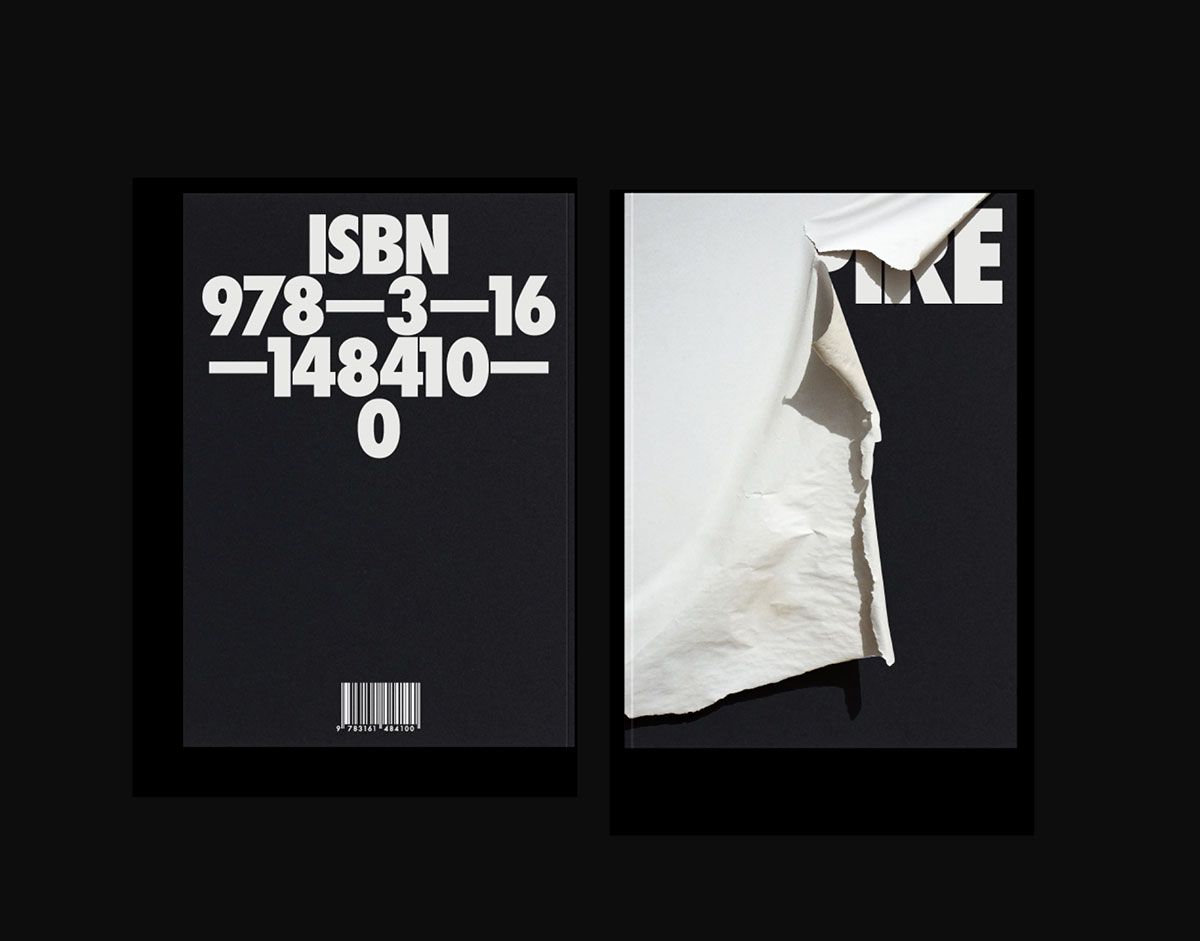

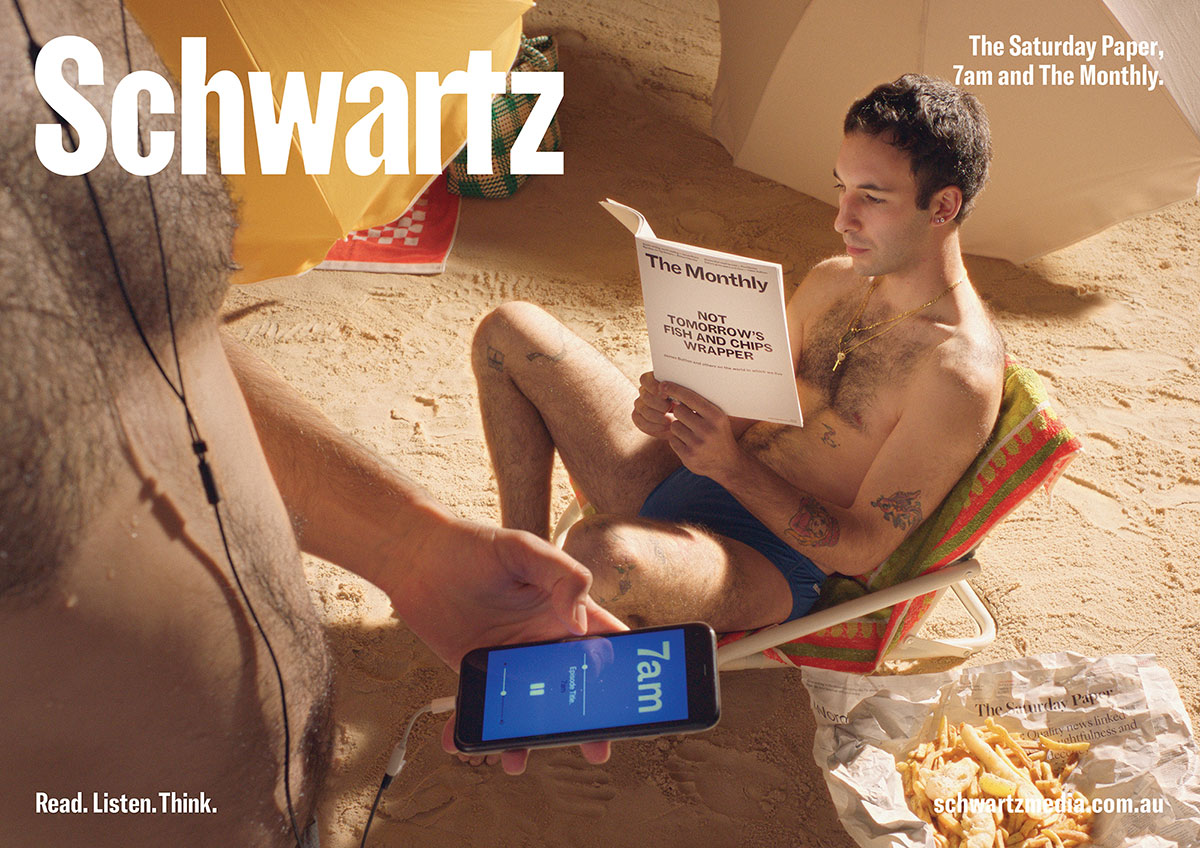

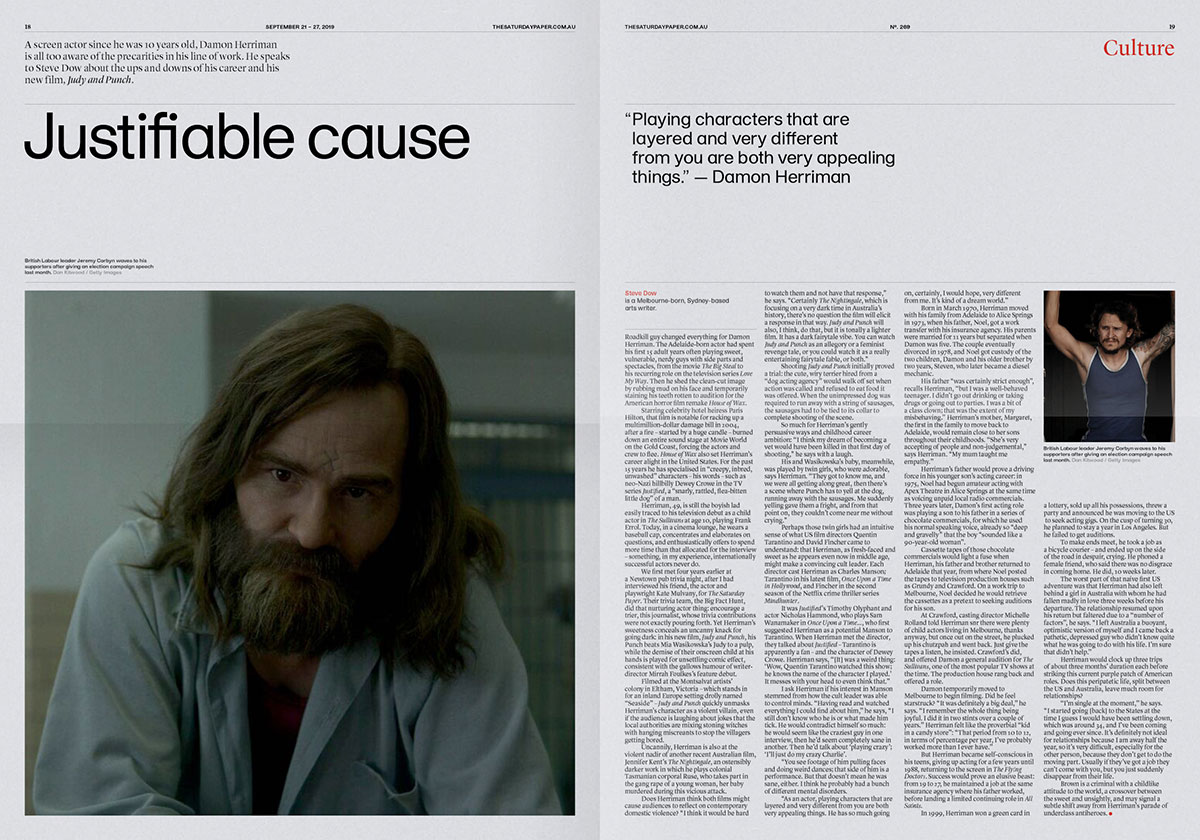

What I love about working on brand identity projects is that over the course of one project I get to do a wide variety of things. This goes from strategy (which involves a lot of research, writing and listening), to naming (which I hate, but that’s life), to concept development and finally onto the implementation/ production of many things like printed stationery, websites, signage, publications, short films, art direction/ photoshoots, campaign development, motion graphics and of course–templates. So, if you consider that I’ve always got anywhere from 3 to 5 branding projects on the go at once and all of them are at different stages of the project, then you can imagine how varied my work can be from day to day. That being said, there are always inevitable periods towards the end of projects where I can easily have a full week where I’m not doing anything creative and I’m predominantly managing production and feeding back on items that are being handled by collaborators and suppliers. This is actually what’s happening at the moment, where I’m in the final stages of 4 projects, but luckily I’ve had to start on a couple smaller ones at the same time, so it’s not all red pens, markups, long emails and stressed out clients.

What is your favourite part of working in communication design and why?

I like to help people and communication is the one thing I’m somewhat good at, so it’s the best way I can help.

I tend to work with clients who are in the creative services or the arts and creatives are notoriously bad at being able to sell, promote or even articulate themselves clearly.

I can help creatives cut the crap and get down to the essence of who they are and what makes them unique amongst a specific group of others.

Hopefully this work helps them to succeed in doing the things they want to do and with the people they wanted to be doing the things with.

In more lofty/ ambitious terms, I think there’s huge opportunity to make a genuine difference in the world. I mean, you have to be prepared to play the long game, but by a constant chipping away with consistent attempts at challenging the status quo—the expected and the conventional—over time communication designers can make a real difference towards influencing more responsible consumer behaviour. Or, at least that’s what I keep telling myself.

What role does collaboration play in your design practice?

A valuable one!

While I do work relatively autonomously, client collaboration ends up being the major one. Of course, working collaboratively doesn’t mean I try to make things easy for my clients though. Outstanding project results can only be achieved when a client is willing to put in the hard yards.

I try to avoid working with people who have that “can’t you just sort it out?” attitude.

Beyond client collaboration, every project I undertake requires a team to complete. The team varies per project but there are some constants like my website developer Sam Morgan, who I’m always working with on multiple projects at once. It’s become such a fluid process over the years and in the occasional scenario where my client has dictated the developer, I’m quickly reminded why I can’t take Sam for granted.

I always jump at the opportunity to work with amazing art directors like Marsha Golemac, who I’ve collaborated with on a number of projects over the years and also Coco and Maximilian, a super talented directing duo.

And then there’s a raft of really technical partners who help me with the InDesign, Word, Excel and email newsletter templates, which are all regular components of my projects. One area that’s becoming more regular is collaborating with motion graphics and 3D designers which is awesome. I’m a bit of a self-taught After Effects hack but whenever I get to work with my mate Pat and watch him in Cinema 4D, it twists my melon to see how all that stuff is created.

Ultimately I try and work with people who’s approach and skillset suits the project and that I’m on the same page with. I find it’s best to bring people in on projects where I can just let them loose to do their thing. I’m not really a good director, I’m good at the big idea but how that all comes together, I’m very happy to let that be driven by whomever I’m collaborating with.

Putting your trust in others is beneficial for everyone and will always produce the best outcome.

I’m really looking forward to working with another mate (Dale Hardiman) on a piece that’ll be displayed in an exhibition curated by Alt Material called “Community” (each designer is allocated a vacant shop to create a response to the theme) as part of this years Melbourne Design Week. I’ve never had the opportunity to do anything of this nature (object/sculpture/installation) before so it’s really exciting!

When working with a new client, what is the most important part of the process when setting out on a new project?

In terms of new clients and new projects, it’s definitely the first couple stages.

The “brand DNA” work that happens in the beginning really sets the tone of everything—it’s the foundation.

I’ll talk more about this stage further below.

More broadly speaking though, the final stage is equally as important as it’s generally where the wheels are wobbly and threatening to fall off the bike. As a result, I’ve learnt to try to pace myself and save some energy. All too often and not for lack of harassment, final content comes through quite late in the process and it’s rarely supplied in a manner that’s exactly how things have been set out. You need to have some beans left to make sure the design intent is maintained as best as possible right through to the end. It sounds obvious but when you’re one person juggling a pile of things at once, it’s easy to let things slide. The too-hard basket often sings its sweet siren song, beckoning me to the serene surrounds of the CBF club.

In your lecture, you spoke about how important identifying a client’s values can be for coming to a successful visual identity. Yet this also sets the stage for the working relationship. How do you do this at the start of a partnership? And how have you worked to identify and communicate your own business values?

I think it’s just sort of happened over time. In the early days there were definitely a fair few clients where our values weren’t aligned and while I probably knew it from the outset, I took on the project anyway, usually for financial reasons or because I used to be terrible at saying no. Most of those projects ended up ok, but there have been a couple client relationships that I had to terminate before completing the project. Which is not a decision to take lightly but if you find yourself constantly losing sleep over one particular relationship or project, and if you can afford to walk away, then I’d absolutely advise doing so.

Life is too short and it’s not good for your mental or physical health to be in a bad relationship regardless of whether it’s in your work life or personal life.

This is not to say things are currently perfect and I’m only working with clients where all values are aligned—that’s a tall order and I’m not in a position to exclude everyone who doesn’t feel the same way. There are too many other factors involved in deciding whether a project is a good fit or not, so I still follow the 3 F’s. This means that each project is benchmarked by whether it will be something done for “fun” or perhaps the budget is just too good to pass up (these are far and few between) and thus taken on for “fortune” or will it be “fame” that lures me in? The latter is less about fame in the traditional sense but more-so around building a strong portfolio in one specific area. For instance I’ve been consciously working heaps in the architecture and design sector, so the more good projects of this nature I can take on, then the potential to further cement my position as the “go to” in this area is greater.

There’s also a fourth F and that’s “friends,” which do still make up a small portion of the work I take on. It’s always got the potential to blow up in your face and destroy the friendship, but if I think I can also get something out of it as well, I’ll generally take it on. With friends—stating the obvious—generally there is absolute alignment in values, so that helps.

In terms of how I communicate my values beyond what’s evidenced by my output, I reckon that’s mostly happened on social media.

Things like Instagram enable me to post work in sort of a case-study like fashion, while I try and use stories as way to express more of the values and personality side of my practice.

I always say my website was designed to act as more of a deterrent than a new business tool, but I suppose that in itself is a communication about me. A potential client recently said I came across as “edgy.” Lol.

On the subject of values, during your lecture, you suggested that originality should not be a huge concern within the design process but rather whether the work is appropriate for the client’s needs. Can you extrapolate on that and explain how keeping the concern over originality out of the design process plays out?

How much time do you have? I suppose this is really a comment about a few things and it might come across as a bit all over the shop, but here goes.

First, there has aways been, and always will be designers who are bored with the current status quo, bored with what they just finished. These people are hell-bent on newness, the next, let’s do something different for different’s sake and fashion for lack of a better word. To me it’s often fleeting and this instinct also runs the risk of becoming more about a designers ego or individual ambition than what the client or project requirements actually dictate. In other instances, the project requirements may actually dictate originality. For example, I often get, “We want a brand unlike anything ever seen before” but is that really the right approach?

How many truly innovative businesses, products or services are there? Of course they exist but they are in the minority.

My point here is that our design responses should always be an appropriate reflection of the client and their ambitions.

If the client is wildly different and innovative, then our response should attempt to be wildly different and innovative. If they are batshit boring then the response should champion that and not try to make the reality something that it isn’t. There are countless ways to make a boring business interesting without resorting to tactics that are either disingenuous, misleading or simply an exercise in window-dressing. It’s this lack of restraint and judgement that can lead to a brand that isn’t authentic or related to the actual customer experience.

We have a responsibility as designers to make sure we are not misleading consumers by creating design responses that are laced in emotional ploys and tactics engineered to make consumers feel a certain way in order to influence a purchasing decision. This is obviously difficult given so much of our legacy is about precisely this task, and it’s what many clients hire us to do! But I often reference the work created by KesselsKramer for the Hans Brinker Budget Hotel in this regard. It’s a perfect example of how we can use honesty (although taken to a hyperbolic extreme) to sell a product or service in a way that’s both authentic and original. I mean, original to a degree, you could say Volkswagen originated the whole honest and self-deprecating approach but who cares, frankly, we need heaps more of this in the world.

If all brands became unoriginal by being more honest, then this would absolutely be a better world than the one we live in now.

I think there should also be consideration towards the shelf-life of originality. Brands like Nike have the pockets to always be investing in innovation and commission a million different creatives to constantly extend/ evolve the brand and thus they have a legitimate need to always be original, new and different. But for the vast majority of small to medium-sized businesses, they absolutely need to get as much bang for their buck as possible. Even if they’re spending as little as $20k on a rebrand, that’s still a lot of money for them and I’d guarantee they’d want that work to look relevant in 5 years time at a minimum. I regularly see great pieces of “graphic design” that I’d call original, but I also struggle to see those designs standing any test of time. Of course not everything needs to, but a large chunk of branding work should probably not feel dated after a couple years when what’s in fashion changes again. Sometimes originality and longevity aren’t always good bedfellows.

I’m by no means saying that it’s ok to copy things, to rip anyone off or that we shouldn’t be striving to create work that makes people see the world in a new way, but for me, with my work, it’s very much about burying my head in my client’s sand—which sounds a bit saucy but you know what I mean. I put a lot of energy into looking inward and making sure we’re really focussed on words that help to express all the qualities uncovered in the brand DNA stage around who my client is and what makes them unique. My client’s output itself might not be terribly unique amongst their competitors and thus not worth building a brand around, but who they are as people always is and that’s what I focus on. I think my strength is in bringing my client’s personality to the forefront. Whether the resulting visual aspect of that brand looks like something else in an unrelated sector then I’m not too fussed. As long it’s unique amongst my clients’ competitors and is an authentic reflection of them, then that’s what I’m striving for.

You showed the Shillington students an insight into the way you present your working process to new clients. While you don’t have to go into the same detail here, when did you begin offering this as part of your working relationship and how has it positively affected your work as a designer?

The process that I follow now started with my first independent project.

Not all projects require or have the budget for the full extent but even with the smaller identity projects, I try to implement a pared-back version of the initial DNA stage and use that to create a really solid brief. The thing about this DNA stage is that, as much as it is about getting the foundations right in a predominantly word-based manner, it also attempts to remove any baggage a client might be bringing with them. That baggage can be emotional (from having previous bad experiences with agencies), or visual. I sometimes have clients that have already put some mood-boards together or come to me saying “Hey I’ve got this idea…”

I want us to start this journey together fresh, with no baggage. I want us to take a couple of weeks to really get to know each other, clear the mind of any preconceived visual noise and gradually let the process evolve and become visual. Even if we end up with something that looks like a reference from the mood-boards that I said to forget about, then that’s great, it’s a win win but we’ve gone through the process and we’ve come to that solution as a legitimate outcome, rather than just starting off trying to make one thing look like another thing.

Process is as much about a journey of discovery as it is about instilling trust and demonstrating that you’re capable of thinking before acting.

Running your business solo means the daily management of business admin, including maintaining client relationships and communications. What advice would you give to new freelancers on how to manage this part of running their workday, without derailing their ability to do great design work and meet deadlines? Any tips and tricks?

Yeah, this is the hardest thing about being a sole practitioner and there’s no easy solution, at least that I’ve found. I work long days (12 to 14 hours on average) and generally another 6 or 8 hours over the weekend but it’s really the only way to keep projects on track and at a quality that I’m happy with.

Time management is everything. You have to be really organised and disciplined.

I plan out my following week every Friday and then refine constantly, like at the end of the day I allocate time to each task I need to do the next day. The toughest bit is trying to stick to the allocated time, like when you’re on a roll with the creative but you need to put it down to artwork something that has to go to print, ring a client back or put together a fee proposal.

I’m always trying different arrangements with time but you eventually get to a point where it all feels like an exercise in futility. You can plan your time down to the minute and you can ride your clients like a jockey but no matter how many measures you put in place, things rarely go to plan. You kinda just need to plan for things not to go to plan.

Tracking time in general is super important. I remember dreading timesheets when working at other studios and always thinking they were pointless but it’s the best way to understand a few things.

Primarily, time sheets have been helpful in working out how much a project should cost.

Time really is money and after you’ve completed a range of projects for a few different clients and you’ve been tracking your time, you can better understand how much time you need to do the work the client has asked you to do. Thus it’s easier to put a dollar figure around it (total hours required x hourly rate = fees). Of course clients often come knocking with a budget in hand, but if you haven’t figured out how long things tend to take on average, you don’t really know how big of an investment you’re about to make and how much money you could be losing.

Knowing how long things take you also simply helps with resourcing and planning. I nearly burnt myself out after the first year of running my own practice because I took on too much work at the same time.

I was worried I’d lose a project if I said I couldn’t start right away and sometimes I did, but in the long run, losing a project is better than losing your mind.

That will happen eventually, but best to try and milk that sweet sweet mind for as long as you can though.

Is there any other advice you would give to designers who are graduating right now or just kickstarting their careers?

I put the below together in 2019 and while it might seem lazy (I mean I am being lazy here) but I think my advice still stands true in 2021.

Be prepared to:

- Make presentations for the rest of your life.

- Get rejected often. This is one of the hardest things to mitigate as a designer. To be great, you have to throw yourself at and put everything into the good projects, while attempting to keep enough distance from your work to avoid the soul-destroying, emotional bodyslam of having your work rejected.

- Execute ideas that you do not fully support or believe in. Whether they come from the client, your creative director or your colleagues, this is inevitable. The best you can do is always put forward alternative ideas that you do believe in, alongside the ones you don’t and then see point 5.

- Sell your ideas. If you’ve ever watched Mad Men then this is about channeling your inner Don Draper. You can even bring a box of tissues with you to the presentation so the client has something in arms reach when you bring tears to their eyes with your genius creative and compelling argument around why your approach is genius.

- Understand that design is delivery. It’s not the idea, the sketch or the Instagram tile, it’s being able to see an idea through to the end, delivering what you agreed to, on time and on budget. (I’ve lifted this from one of my architectural clients but it’s completely relevant for all designers).

- Change everything.

- Learn to write. Most designers can’t, at least not very well. This will not only make you look competent, it will help differentiate you from the others, who can’t write very well.

- Spend a majority of your waking life thinking about your work, because your work shouldn’t be work, your work is your practice. You must be invested. It’s like KRS–One said, “Rap is something you do, hip hop is something you live.”

- Have fun. Work hard. Be nice to people. (Credit to Anthony Burrill there, but it’s so true. It’s pretty hard to solely compete on the uniqueness of your output but being a pleasure to work with is what will keep clients coming back to you).

Huge thanks to Mike for a super inspiring lecture to Shillington Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne, and for sharing so much of his wonderful experience and knowledge with us here. Make sure to follow M.Giesser on Instagram and check out the studio’s website.

We’ve hosted some of the world’s top creatives, design studios and advertising agencies at Shillington. Check out more interviews from guest lecturers.

Want to win some amazing prizes and stay in the loop with all things Shillington? Sign up to our newsletter to automatically go in the draw.